Myth, the power required to unite a people, but what is it? From the Greek word mythos, meaning a narrative tale, a myth is a story used to explain the origins of something, often infused with fantastical and divine elements. The common myth at the heart of the culture of a certain people is what often binds them, uniting them in thought and in origin to a single event or tale, forever giving them a shared identity.

In a tale as old as time itself, the origin of the fantastical and the mythological often begins with the ordinary and the mundane. From man to legend, and from legend to man, people are thrust into greater and greater stories until the originals are lost and the accounts of their deeds have transformed into something beyond mortal capabilities. The men who become legends and eventual myth, are those men who do legendary actions worth recording. Whether the actions are good are bad is left to the people in their posterity, garnering the title of either hero or monster.

The names of great men are those names which have been recorded in the annals of history by their friends and cohorts to be passed down for generations. The actions and exploits of heroes are meant to be like a model for future men, growing up as adolescents with paths to follow and molds to shape themselves into. If boys were given champions to follow whose stories did not reach into the realm of the extraordinary, then those boys would not try to reach into the extraordinary themselves. It in this simple view of heroism that courageous men find themselves in the pit of despair, where they are given the choice of cowardice and disgrace or courage and honor, and through great suffering and cost to themselves create deeds worth emulation.

One such man hero has not been forgotten, and his story begins in medieval times, in the late 8th century AD in Francia, a Germanic kingdom and home of what is now modern day France. Just half a century prior, the expansion of Islam was checked for the first time ever at the battle of tours by a man named Charles Martel, his name quite literally meaning Charles “The Hammer.” This man sired two heirs, Carloman and Pepin the Short, and the latter eventually sired Charlemagne, the then future first Holy Roman emperor. Many noble men rose and fell in the time between Charles Martel and Charlemagne, and many men were still yet to bring glory to their name and to their God. One such man was said to be the nephew of Charlemagne, and close friend Roland.

This is the legend of Roland, one of the twelve holy paladins of Charlemagne, champion of Francia, wielder of the legendary sword Durendal which was said to have been given to Charlemagne by an angel at the vale of Moraine, who subsequently gave it to Roland. Other stories tell of how it was crafted by the legendary Wayland the blacksmith, crafted with the teeth and hair of saints with the cloth of the garments of the virgin Mary herself.

On the return march home, after many small battles in the lands of Spain, and after sieging castles in the name of God, Charlemagne and Roland received an offer from the Muslim governor of Zaragoza, a city they had lad siege to for over a month. The offer was that if the King and his champion along with all of his men were to withdraw from his lands, they would receive a large sum of Gold and safe passage home. Charlemagne accepted knowing that his men were strong enough to withstand any attacks from the Saracens, and had secured a foothold in Northern Spain for the Frankish people.

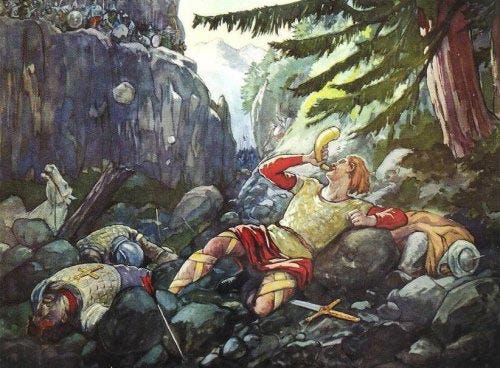

However, on the return home through the Pyrenees they were attacked at Roncevaux Pass, a small meadow pass surrounded on all sides by mountains. In the difficult terrain the rear guard led by Roland was cut off from the main force of Charlemagne. Refusing to blow his horn, oliphant, and have Charlemagne turn around into the danger of the ambush, Roland fought back the Saracens with his legendary sword durendal, slaying many times what any ordinary man could. His men begged him to blow his horn for relief from the main forces, but he refused, killing more enemies instead and standing his ground. After cutting of the hand of one leader and beheading another, and slaying hundreds if not thousands of men, Roland received a mortal wound. Not wanting durendal to fall into enemy hands he tried to destroy it, but the legendary sword was indestructable. Then he is said to either have thrown his sword with all his might sticking it into the side of a mountain. Cursing the cowardly Saracens that ambushed him by blowing his oliphant with his last dying breath.

So goes the many versions of the tale and Roland’s heroic deeds, saving the father of Europe himself, Charlemagne, the future emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. These mighty deeds however have been twisted with time, and exaggerated with the passing of eras. Roland was a great warrior, and one of Charlemagne’s most trusted men, and the battle of Roncevaux Pass was a tumultuous battle that ended up taking the life of Roland and the rear guard, but what of the details? Here is the true story of the true man who we have brought into a legendary status and near mythological stature.

A war was raging between two Muslim factions, that of the Abbasid Caliphate in the East, and that of the Ummayad Caliphate in the west. A man by the name of Sulayman al-Arabi of the Abbasids was feuding with Abd ar-Rahman I of the leader of the Ummayads, and sent for delegation with Charlemagne at Paderborn in modern North Rhine-Westphalia Germany, promising great reward and military reinforcement if he was able to drive out Abd ar-Rahman I from his lands, he could have a portion of them. Charlemagne viewed this as an opportunity to expand Christendom back into its former lands of Spain, and al-Arabi viewed Charlemagne as a wedge force to give him and his men an upper hand. Al-Arabi swore the allegiance of him and his men to Charlemagne, and Charlemagne accepted. So began the march south into the Pyrenees.

Initially marching into Northern Spain, which was controlled almost entirely by the Basque people since ancient times and their domaine has since contracted from Northern Aquitaine down to the borders of the Pyrenees, most of the Basque were relectant but accepting of Charlemagne, giving up what Muslims they harbored in their cities. The Frankish forces however looked down upon the Basque people, as they were heathens, pagans of the old world, and would not convert to Christianity until somewhere in the 10th century AD en masse. The Franks were harsh in their taking of these cities which otherwise were accepting of their being taken in the first place. This would otherwise go unnoticed, if they had not returned.

After marching past the regions of Wasconia, the region of the Basques, and heading further South, Charlemagne conquered city after city including Barcelona and Girona, eventually coming to the agreed upon city of Zaragoza. Having pushed Abd ar-Rahman I’s forces out, he was going to enter Zaragoza and claim his reward and leave. Instead, the new governor of Zaragoza and ally of Al-Arabi professed he never made allegiance with Charlemagne, and refused to hand over the city. Laying siege to the city for over a month, Charlemagne and Husayn both grew weary, and Al-Arabi was on thin ice with Charlemagne for having deceived him in his eyes. With the offer of a large sum of Gold, Husayn was able to persuade Charlemagne to cease the siege and let the captive city go. It was time to march home back to Francia.

On the way back, Charlemagne wished to secure his position in Spain, and decimated the cities of the Basques along the way, as they were believed to have colluded with the Saracens in the first place. He burnt down several cities and tore down the walls of Pamplona, the capital of the Basques, murdering thousands along the way. This was the mistake, their return to lands that they did not know, and the smearing of innocent blood. On their way back through the Pyrenees, a large mostly peasant army of Basques ambushed Charlemagne and his men, routing the back half of the army. Their goals were not clear, but it was probably a mixture of both the Gold their horses were carrying and revenge for their city and kinsmen. Roland and the Franks were caught offguard in such a mountainous region and slain, not before killing great numbers of Basque. Charlemagne eventually came back for Roland after the battle, to weep over the body of his favorite general, Roland. Never again would Charlemagne seek to expand further into Spain, for this scar on his name and family would be burned into his memory forever.

So is the true story of Roland, the great Paladin of Charlemagne. Eventually this march south into Spain would become the basis and ideal for the reconquista of Spain which would happen shortly after and last well into the 15th century. Roland, with time became lionized as the defendor of Christendom, the great warrior of the Holy Roman Empire and of France. Songs were written in his name, and embelishments were added to the story. Eventually the Basques were wiped from the story, and they were replaced with tales of Moors, the true enemies of the Christians.

Time rolled on, and details were changed, man became a hero in death, and through death he became legend. In time these legends became mythological and magical in nature, powerful artifacts of the past meant to inspire the youth of armies throughout all of Europe, for the roots of the Holy Roman Empire and Charlemagne ran deep through the blood of Europeans, uniting them in their tales of this heroic man; and so man becomes Myth.

This week me and my good friend wrote both of our stories together about man and myth. Here is an excerpt from his story on the matter.

"But the boy was boneless, and it felt as though there was only gristle where the bones would be. And while he was still young, his height was such that there were few men as tall as he was. He was the handsomest of all men, and so wise that it is unlikely there was ever a wiser man than he was."

Thus is the birth of Ivar the Boneless in The Saga of Ragnar Loðbrók. What does this Son of Ragnar have to do with a Danish invader mentioned in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, or a Hiberno-Norse King of Dublin? Is this one man's story growing in the telling, or just blind coincidence? “

If you’d like to read more, go to his post here.