In honor of Shinzo Abe and his recent assassination, I write these words. With the opening and closing of every age comes the passage of violence through which every era is realized. Every culture has had their warriors, their version of violence, and their rites of passage, but since the specialization of the industrial era and the monopolization of violence by every state, the average man has forgotten what it means to be a man in the full realization of himself.

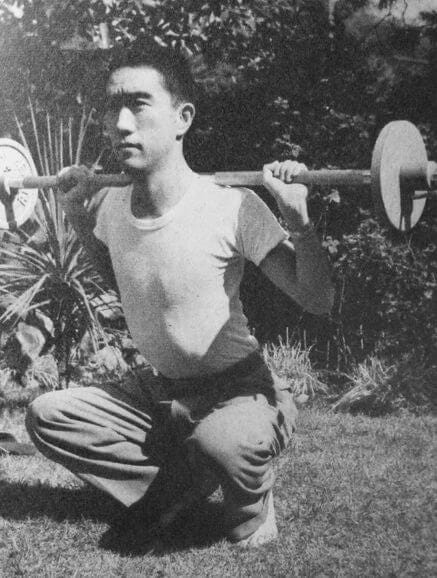

Yukio Mishima, born the 14th of January 1925 in Tokyo City of Tokyo Prefecture Japan looked to a hidden past to realize what was missing in modernity. An author, a poet, an actor, a nationalist, a shintoist, and most importantly an overlooked warrior, Yukio combined many ideals of a previous era of Japanese society into an era of tumult he found himself existing in.

Many formative events took place in the early years of Mishima, but an often misunderstood portion of his early years that transformed his life was this.

The 27th of April, 1944, Yukio Mishima received a draft notice from his state at the young age of 19 to join the imperial Japanese military. Shortly before his medical examination on convocation day Mishima had contracted a cold and during the day of convocation his doctor misdiagnosed him with tuberculosis. This resulted in his receiving the rank of “second class conscript,” which prevented him from serving.

This was massive for Yukio Mishima, not because his unit which he was supposed to have joined died mostly in the Philippines shortly there after and the world would have missed his writings, but because he wrote mostly because he had missed his opportunity to experience a warrior’s death, and this forever changed the way he viewed life and the way he sought to live his own.

Yukio had been a child of weak constitution, and for him the meaning of world and things was being corroded by the words we assign to them. Detached from reality by the thoughts and things we attach to meaning to communicate to one another. Mishima wanted something more real, eternal, withstanding the tests of time in a sense. For Mishima, there was something missing, until he discovered sun and steel.

“What I lack is an existential awareness of myself and of my body. I know how to despise mere cool intelligence. What I want is intelligence matched by pure physical existence—like a statue. And for this I need the sun, I need to leave my dark, cave-like study.”

Mishima had through the course of the military and exercise discovered something to grasp the world with, the actions of reality. What Mishima wished to describe in all of his beautiful prose was his disconnect from reality through his simple bookish existence. He felt as though reality was something entirely foreign to his thoughts, and because of this, he ascribed pain to simple words, and they missed the true mark of measure he gave reality but had yet to experience first hand.

When you began to exercise and learn of the limits of your own existence, did you understand this? Did you feel this way?

If you have not yet picked up the steel and found the sun shining upon your body, embracing you in the light of reality, think about what is stopping you and crush it.

When Mishima discovered exercise, that simple truth of lifting iron and the force it puts on the muscles as gravity itself tries to pull the body downward, and the body must resist this urge to give in to weakness and pull upwards with all its might to overcome the obstacle, he discovered what he was looking for. Leaving behind his cool dark study full of books, he continued to read in the sun, exercised outside, embracing the other end of the dead samurai spirit of the warrior-poet, like that of Ota Dokan of 15th century Japan.

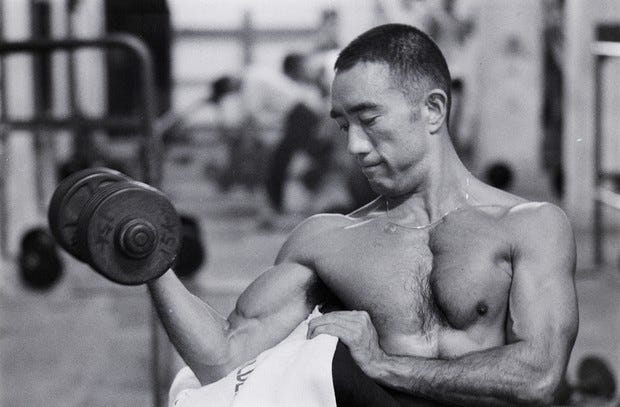

“It is true enough that when I lifted a certain weight of steel, I was able to believe in my own strength. I sweated and panted, struggling to obtain certain proof of my strength. At such times, the strength was mine, and equally it was the steel’s. My sense of existence was feeding on itself.”

Mishima was learning the path of sun and steel, finding his own existence through direct experience. He learned to live as the men he once read about, great warriors from the past, the warriors he wished to live as but was rejected the ability to live as when he was unable to serve in the Japanese military and die a warrior’s death.

As a man that started as weak he grew out of his mental existence as only a book reader and student of knowledge and grew into his physical existence. He realized many things and began to reflect on his own past, one where he could look back from the lense of experience where he had known both the mind and muscle, pointing to the flaws and shortcomings of those bookish men who only live in the world of words.

“Here, I felt, I was gaining a clue to an inner understanding of the cult of the hero. The cynicism that regards all hero worship as comical is always shadowed by a sense of physical inferiority. Invariably, it is the man who believes himself to be physically lacking in heroic attributes who speaks mockingly of the hero; and when he does so, how dishonest it is that his phraseology, partaking ostensibly of a logic so universal and general, should not (or at least should be assumed by the general public not to) give any clue to his physical characteristics. I have yet to hear hero worship mocked by a man endowed with what might justly be called heroic physical attributes. Facile cynicism, invariably, is related to feeble muscles or obesity, while the cult of the hero and a mighty nihilism are always related to a mighty body and well-tempered muscles. For the cult of the hero is, ultimately, the basic principle of the body, and in the long run is intimately involved with the contrast between the robustness of the body and the destruction that is death.”

In this paragraph from Sun and Steel, we find the true message of Mishima. This observation that cynic academic weaklings mock men with imposing figures brings attention to the disconnect of man from his world. Men have lost their way, and in the search of knowledge and greater and greater heights of academia, have lost sight of their true nature. He is trying to show the reader through all of his texts and most importantly his own body which he had modeled after his own thoughts, that life is meant to be lived with mind and muscle conjoined into one unitive body of action. He wanted a world of pure existence where thoughts represent reality, and words the world, by grasping and siezing the world of the living through sun and steel.

Return, o’ man, to the world of the living. You have within you the blood of men who siezed life to live, and you should not waste it. Put down your idle thoughts and pick up the iron that rejects your weakness. Firmly embrace the world you live in and create the country of your sons, and your sons sons, for a great lightning lurks on the edge of this darkness, and you need to be ready for the coming of that lighting.

Tennō heika banzai